A West Virginia Christmas Mystery for the Ages

I know that the post-Halloween holidays are not generally marketed towards us spooky people, but just because everything is merry and bright, that doesn't mean the terrors have stopped lurking beneath the surface. In addition to Krampus and Gryla, occasionally real life is scarier than folklore, and that leads me to one of the most chilling Christmastime stories I've ever heard.

In the early hours of Christmas Day 1945, a two-story timber frame home in Fayetteville, West Virginia was reduced to ashes. The residents, George and Jennie Sodder and four of their ten children watched their home burn, leaving only the foundation and unfortunately, mystery upon mystery to unravel.

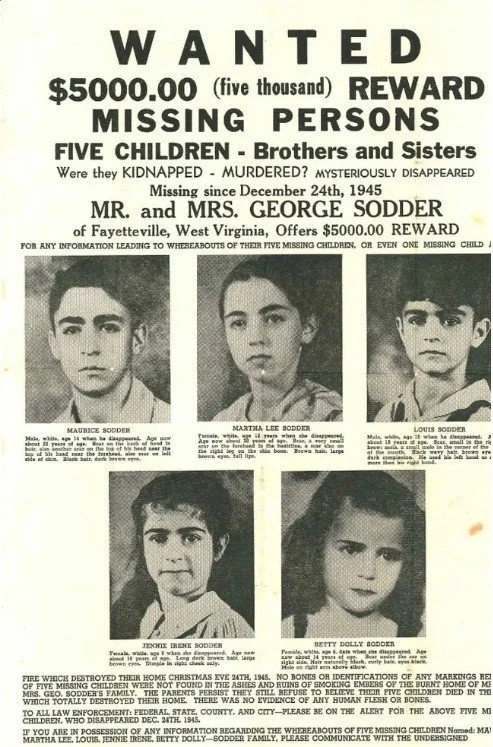

You see, while George and Jennie were able to flee the fire and John (23), Joe (21- away in the Army), Marion (17), George Jr. (16), and Sylvia (3) also escaped harm, their other five children were never seen again. While many, including the authorities, assumed that Maurice (14), Martha (12), Louis (10), Jennie Irene (8), and Betty (5) perished in the blaze, it's not quite that simple.

Before I give you the details, let's rewind and take a look at the circumstances surrounding the Sodder family, the fire, and the possible disappearance of the five young children.

Medium.com- photo of the Sodder house

THE NIGHT OF THE FIRE

On Christmas Eve, eldest daughter Marion gave her youngest siblings new toys from the dime store where she worked. Excited to play with their gifts, Mrs. Sodder consented to letting Marion stay up late with the younger children (Betty, Jennie Irene, Louis, Martha, and Maurice). Mr. Sodder had gone to bed earlier, at the same time as the eldest boys (John and George Jr.), after a long day of work. Around 10:30 p.m. Mrs. Sodder asked the children to be sure to bring in the cows and chickens when they went to bed, and she took Sylvia upstairs to go to sleep.

Just past midnight, the phone rang. Mrs. Sodder ran downstairs to answer it, and on the other line was a female caller, who asked for someone whose name she didn't recognize. She let her know it was the wrong number, and in response the caller laughed, and Mrs. Sodder heard glasses clinking in the background before the caller hung up.

On her way back upstairs, she saw Marion asleep on the couch, but not the younger kids. She also noticed that the door was unlocked, the curtains were open, and the lights were still on. This was unusual for the kids to leave these things unattended to, but she assumed in the Christmas excitement, they'd forgotten and gone up to bed. So she shut off the lights, locked the door, drew the curtains, and went back to bed.

About thirty minutes later, she was awoken once again by a sound she later described as a sharp thump on the roof, then something rolling off of the roof before hitting the ground. She fell back asleep, only to wake again shortly after 1 a.m. to the smell of smoke. Mr. Sodder's office was engulfed in flames and she quickly woke her husband and they rushed into action.

Jennie ran to ask Marion to take Sylvia outside, which she did. Then Jennie and George shouted up the stairs to the attic where the older children had their bedrooms. They heard no reply, but John and George Jr. came down, hair singed, and ran outside. John claimed that he first ran back up to wake his siblings, but then later changed his story, saying that he'd only shouted up the stairs to them, but didn't actually see them. Unable to go up there himself, George ran outside to attempt to reach the children by other means.

He first tried to break into the house by a window, and cut his arm badly in the process, and when that didn't work, he went to retrieve the ladder that was kept by the side of the house. Strangely, and tragically, it was missing. Next, he and his sons went to move their coal hauling trucks close to the house so they could climb on top of them to reach the attic window, but the trucks wouldn't start, even though they'd worked fine just the day before.

While George and his elder sons scrambled to find a way to get into the home, Marion ran to a neighbor's home to call for help. She tried to reach the fire department but no operator answered. Someone who saw the fire from nearby also tried to call, but they, too, were unable to get a hold of anyone.

By 1:45 in the morning, the entire home had been reduced to ashes. It wasn't until 8 a.m. that the fire department arrived, despite being only 2.5 miles from the Sodders. They finally got to the scene seven hours after someone had driven into town to personally fetch the fire chief, F.J. Morris, who claimed he had to wait for another firefighter, because he was unable to drive the truck. Morris activated the "phone tree", contacting another firefighter, who contacted another, and so on.

By 10 a.m., Morris told the Sodders there was nothing left to do. The fire had completely leveled the house, and according to their very cursory investigation, no remains had been found. He did ask Mr. Sodder not to disturb the site, in case any further investigation was needed.

News.com.au- a reward poster/flyer for the Sodder children

THE EVENTS FOLLOWING THE FIRE

By December 29, George and Jennie had reached their breaking point and they could no longer bear seeing the bare foundation of their former home, covered in ash, either that of their house itself or of their beloved lost children. George took it upon himself to load five feet of dirt over the site, in order to create a memorial garden.

The next day, the coroner convened an inquest and determined, with the help of a jury, the fire was an accident caused by faulty wiring. Death certificates were issued for the five Sodder children, and the case was considered closed.

On January 2, a funeral was held for the Sodder children, and while their surviving siblings were at the service, George and Jennie were too distraught to attend.

In the months and years that came after, the Sodders came to suspect that perhaps the fire was no accident, and that their children might not have perished in the blaze, as the authorities had originally determined. For decades afterwards, George, Jennie, and the surviving Sodder children, as well as their descendants, spent countless time and resources trying to find the truth.

In August of 1949, George persuaded a Washington DC pathologist to conduct a more thorough investigation of the site. At that time, the garden was excavated, revealing some damaged coins, a burned dictionary belonging to one of the Sodders, and several pieces of human vertebrae. After being sent to the Smithsonian Institute for study, it was determined that the vertebrae belonged to someone aged 16 or 17 at the time of their death. This made it unlikely, though not impossible, that they belonged to Maurice, who was 14 at the time of the fire. Because the bones didn't exactly match age-wise, and showed no signs of fire damage, it was determined they were likely to have originated in the dirt that George used to cover the foundation for the memorial garden.

In addition, George regularly followed up any potential leads in-person for the rest of his life. Between 1949 and his death in 1968, he traveled to New York City, St. Louis, Texas, and Florida, every time coming up empty handed. We'll discuss some of these leads in just a moment, along with other potential sightings of the children.

After the Smithsonian Institute report, the West Virginia legislature actually held two hearings on the Sodder fire, but afterwards, the governor and the state police superintendent determined that the case was "hopeless" and they ruled that the case was closed at the state level.

George and Jennie did everything in their power to continue the search, hiring private investigators and reaching out to the FBI. The first hired P.I., a man named C.C. Tinsley, uncovered some questionable activity on the part of authorities in Fayetteville. We'll go over this in more detail shortly. The FBI, however, declined to take on the investigation, with a letter coming directly from J. Edgar Hoover, stating that the case was of "local character" and not "within the investigative jurisdiction of the bureau".

Both the Fayetteville Police and Fire departments declined to invite the FBI to assist with the investigation, stating that the case was closed and the children had died in the fire. However, the FBI supposedly DID look into the case as an interstate kidnapping, but because they found no solid leads, the case was soon dropped.

Years later, the family hired a second P.I., and asked him to look into a letter that was received, but he vanished into thin air, providing no update to the family.

In 1952, George used the site of the former home to erect a billboard, offering a reward for information leading to the recovery of any of his children. It remained there until 1989 when Jennie passed away. On a moving note, Jennie spent the rest of her life after the fire tending to the memorial garden and wearing black in mourning of the children she lost.

independent.co.uk- the original billboard at the Sodder property

LEADS TO INVESTIGATE AND SIGHTINGS OF THE CHILDREN

As I mentioned just above, George spent decades traveling around the country to investigate any leads. From the time the children went missing to the time George died, there were numerous interesting tips and reports to dive into, including the following-

In 1949, George saw a photo of ballet dancers in NYC. One resembled his daughter Betty enough that he drove to the girl's school in New York, demanding to see her, but he was turned away.

After the fire, a woman who had seen the blaze from the road reported seeing the Sodder children peering from a passing vehicle as the house burned. Another claimed to have seen them at a rest stop between Fayetteville and Charleston, where she served them breakfast the morning after the fire, and she noted a car with Florida plates was in the parking lot at the time.

Due to the information lining up with the rest-stop sighting, a woman named Ida Crutchfield made a report in 1952 that was taken quite seriously. She claimed that a week after the incident, she saw the children at a hotel she ran in Charleston. She stated that they were traveling with four adult Italians who kept the children from speaking to her. However, this sighting was eventually not deemed credible by investigators, because she had seen photos of the children two years after the fire, which was five years before she came forward.

Reports continued to come in over the years, including one that Martha was in a convent in St. Louis, and one from a bar patron in Texas that claimed to overhear a conversation between two people who made statements about a fire in West Virginia on Christmas Eve years before. George followed up on all of those and even went to Florida to demand proof that a distant male relative of Jennie's was the actual father of the man's children when he saw photos of them and felt they looked too much like his own children.

A woman wrote to the family saying that Louis revealed his identity to her in 1967 after having too much to drink, and that both he and Maurice were living somewhere in Texas. George traveled there but was unable to speak to her. Police, however, were able to help him locate the men she claimed were his sons. Both men denied being the missing Sodder children. A relative claimed that George doubted their denial for the rest of his life.

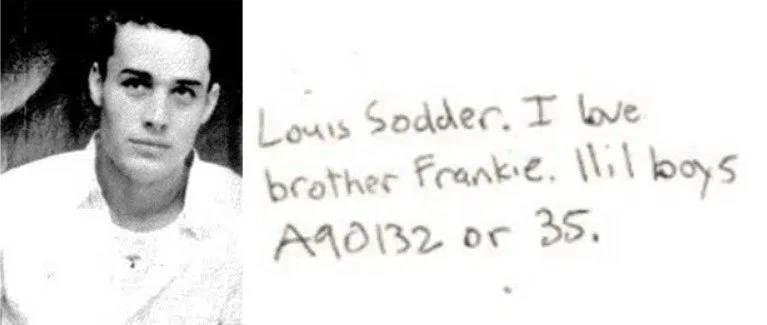

The final lead came in 1968, in the form of an envelope addressed only to Jennie, sent from Central City, Kentucky, and with no return address. The only thing inside was a photo of a young man who looked strikingly like Louis, with the following message on the back:

Louis Sodder

I love brother Frankie

Ilil boys

A90132 or 35

segredosdomundo.r7.com- photo received of "Louis" and inscription on the back

THE MYSTERY

As I mentioned early on, this is clearly a tragic story, but it's also an absolutely wild unsolved mystery. This is in no small part due to the countless strange happenings that began months before the fire and continued for many years.

A mere two months before the incident, in October 1945, a life insurance salesman visited the Sodder home, attempting to sell the family a policy. When George declined, this stranger gave them an ominous warning, claiming the house would "go up in smoke" and "your children are going to be destroyed". The reasoning he gave for this was George's "dirty remarks...about Mussolini".

Mr. Sodder had immigrated to the United States at age thirteen from Italy, essentially alone, settling into life in Pennsylvania, and then later moving to West Virginia. At this time, there was a huge influx of Italian immigrants to West Virginia, and Fayetteville had a small but very active Italian community. While the Sodder family was respected overall in their town, George did have a reputation for being outspoken, particularly about his feelings on Mussolini and the Italian government, which often ruffled some feathers.

Another mysterious stranger visited the house in search of a hauling job (George worked moving coal) and before he left, he pointed to the fuse boxes on the house and said they would "cause a fire some day". George brushed that off, because he had just had the house professionally rewired and inspected. This is perhaps one of those remarks that might seem insidious after-the-fact, now knowing that the house DID have a fire, one that authorities DID attribute to faulty wiring, but perhaps it wasn't as premonitory or threatening as it seems.

In another curious twist, the private investigator hired by the Sodders, C.C. Tinsley, uncovered that the insurance salesman who had given George the ominous threat about his house and children was also on the coroner's jury that determined the fire was an accident due to faulty wiring.

Only a couple of weeks before Christmas, the older Sodder sons noticed a strange car parked along the road through town, the occupants of which were watching the younger Sodder children returning home from school. This lead never panned out, as the boys didn't recognize the car or the person (people?) inside of it.

The night of the fire, there were a series of coincidences that kept George and his sons from getting to the children in the attic. First, a ladder that always rested by the side of the house was missing. It was later found at the bottom of an embankment, 75 feet away from the home.

When the men went to move the coal hauling trucks to the house to reach the attic, the trucks wouldn't start, despite working fine the day before. There were a couple of explanations for this- some believed the hasty starting in the early morning cold weather may have led to flooding the engine. Some speculated that car parts may have been stolen by someone who admitted to a burglary on the property later on.

A phone repairman came after the fire, and he confided to the Sodders that the phone line was not damaged due to the fire, but had actually been cut, leaving them unable to call out the night of the incident. A man actually confessed to cutting the line, saying he thought it was the power to the house, and he admitted to hiding in the Sodders' garage at the time of the fire because he was attempting to steal a block and tackle that night.

This obviously opens the door to SEVERAL questions and theories- why would he climb fourteen feet up a pole to cut the phone line? It also seems unlikely someone would not know it was a phone line instead of a power line. And why would either need to be cut in order to steal something after midnight from a detached garage?

Back to the phone line, it had to have been cut sometime after midnight, which does line up with the burglar's account. This timeline is somewhat confirmed because Mrs. Sodder answered the wrong number call around midnight. Investigators did locate the caller, and the woman confirmed it truly was a wrong number on her part. Another seemingly dead end.

Because the phone was dead at the Sodder's at the time of the fire, Marion had run next door to the neighbor's house to call, and no operator responded, as I mentioned above. A passerby called from a nearby pub, again to no response. Someone drove into town to find fire chief Morris, who activated the "phone tree", contacting (presumably by phone) other firefighters in town. So why were some of the phones not working? Why was no one answering the Sodder's call for distress?

One reason provided for that, and for the lengthy wait for the firefighters to arrive at the Sodder property, is that they were low on manpower due to World War II. But before we give Chief Morris and his crew the full benefit of the doubt, there was some fishy behavior surrounding him and his investigation as well. Remember C.C. Tinsley, the private investigator? He heard that Chief Morris had confessed to finding a heart at the site of the fire and that he'd buried it in a dynamite box on the property.

Tinsley reported this to the Sodders, who demanded Morris show them where he buried the box. After the box was retrieved, the "heart" inside was taken for testing and determined to be beef liver- untouched by fire. Chief Morris claimed that he planted it at the scene to convince the Sodders that their children had perished.

A few months after the fire, young Sylvia was playing at the memorial garden and found a rubber object in the yard, which George identified as a type of hand grenade. This would explain the thump on the roof that Jennie heard the night of the fire which she'd described as "something like a rubber ball". Passerby on the night of the fire also claim to have seen "balls of fire" being thrown onto the roof, something that, while unlikely, could be connected to grenade-like objects being thrown at the house.

On a final mysterious note- Jennie conducted her own tests and research about whether fire could burn hot enough for no remains to be found. This included finding a news report about a similar fire, where bones for ALL of the victims were found. She also burned small piles of various animal bones, and each time, the bones still remained. Lastly, a local crematorium explained to her that bones still remain after bodies burn at 2000 degrees for more than two hours. This is far hotter and far longer than the Sodder fire, where the entire house was reduced to the foundation in only 45 minutes.

Patches Plays Games/Facebook- Sylvia Sodder in 2020

CONCLUSIONS AND THEORIES

With so many unusual circumstances and unanswered questions, the Sodder Children Disappearance has remained one of the strangest mysteries in American history. Many believe the children did perish in the fire, but that doesn't stop others from coming up with their own theories about what happened.

The surviving Sodder children and their own descendants continued to investigate, and developed their own theory. They believe the local Sicilian mafia tried to recruit George, and he declined. Then they tried to extort money from him, and they refused. The children were kidnapped and the house set ablaze as retribution.

The theory is that the children were kidnapped by someone they knew, someone who came in through the unlocked door and alerted the kids to the fire before offering to take them to safety. This would explain why the kids would have left with someone else, and there were actually similar situations where children were taken from a house before a fire, and then, unfortunately, killed after being kidnapped.

If, and this is a big if, the children survived that fateful Christmas morning, and if (another big if) they had lived their lives elsewhere, under new names and new circumstances, the idea is that they chose not to contact their family in order to protect them from any further danger. Obviously, this is all a stretch, and it's hard to imagine that any of this would be truly the case, but we all know sometimes the truth is stranger than fiction.

With the death of Sylvia in 2012, and none of the original Sodder family members living, we may never know what actually happened that night or why, but obviously the tragedy of this young family in West Virginia will never be forgotten.